“The stars we are given. The constellations we make. That is to say, stars exist in the cosmos, but constellations are the imaginary lines we draw between them, the readings we give the sky, the stories we tell.”

Constellations, 2016

On a dark night, if I turn out all the lights, I can see the stars from my kitchen window. I know, of course, they are just little bits of light sent from long ago finally hitting my eyes at the same time—a science fact that never ceases to amaze me—but I want them to be more than that. So in that moment, as I look out from my warm, quiet perch in the kitchen, their light becomes part of the ancient map I see behind my eyes. They take up a spot in my brain and are assigned meaning, before I get a chance to remember what they really are. They root me: locating me in my world, in time and space.

We chart all the stars now, making them explain our ideas about science and math and forever, but once upon a time we turned them into constellations shaped like hunting dogs and herdsmen, used them to remember when to plant our seeds or reap the harvest. The stars can tell stories that comfort us while we wait for the world to stop spinning.

We look for and find meaning given only fragments of information. A gesture, a sign, the arrival of a bird is a message from the dead. We see Jesus in a piece of toast. We fall in love with someone because he looks like someone else. Stardust. Our brains make these leaps of logic all the time. We extrapolate. We fill in the blanks. We can’t help it.

I want to draw attention to this primitive seeking: the innate desire to find order, pattern and connection from a montage made up of these little moments. I am watching my characters closely as they age and change. If I illuminate certain details, will I find some truth, an underlying structure, a map, that will give me the story I crave? Or are the visual patterns just that: here a line flows through many images, a colour that continues from frame to frame, forcing a connection where maybe there is none?

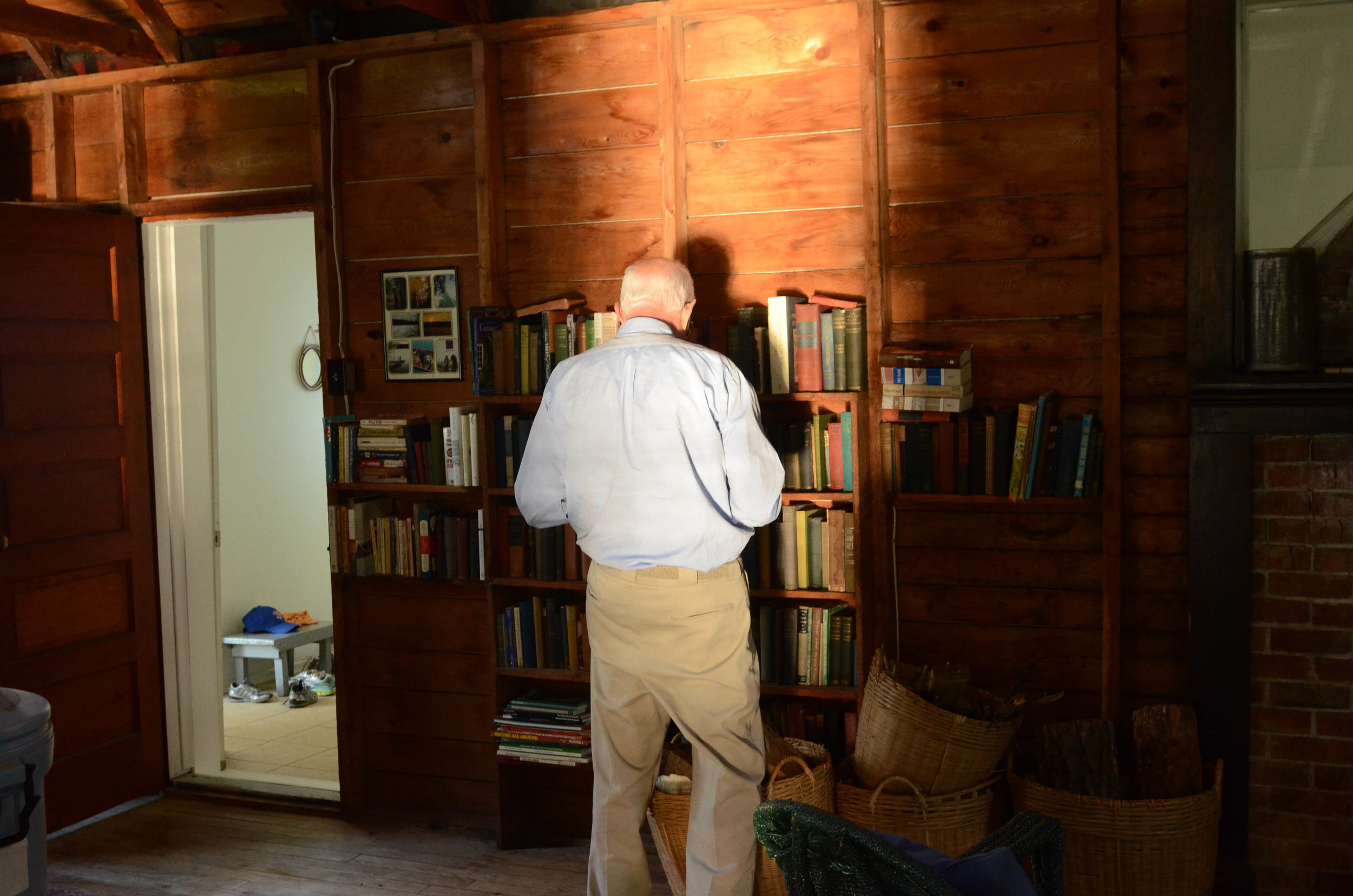

Vigil, 2012

Plants can be difficult: they are strangely shy in front of my camera and I am often awkward in front of them. I want to portray their melancholy, their ambivalence toward us, their alienation from the natural world, their longing to be wild. Sometimes they frustrate me, and then I leave them to wither. But they keep drawing me in with their sad stories.

Plants try so hard to communicate for us, I think. They arrive in our lives as a gift, an apology, a leftover centrepiece, an offering, a burden. How can they seem so benign and forgettable when they often stand for words we can’t say?

The Pity of Lost Things, 2001-2002

The clothes in these photographs have long been outgrown. They are hand-me-downs now or rags, even - but once upon a time they were the most loved outfits in your closet. A little too big or a little too worn, they were somebody’s favourite nonetheless. Some picked by parent and some by child, these suits and ties, fancy dresses with matching socks, a hockey sweater -- these were the lucky ones, outfits chosen over others to adorn little bodies for class photo day. Some pose awkwardly, instructed as they were, to place hands on knees or stand up straight. But the formality and anonymity are broken here and there when rebel souls goof for the camera.

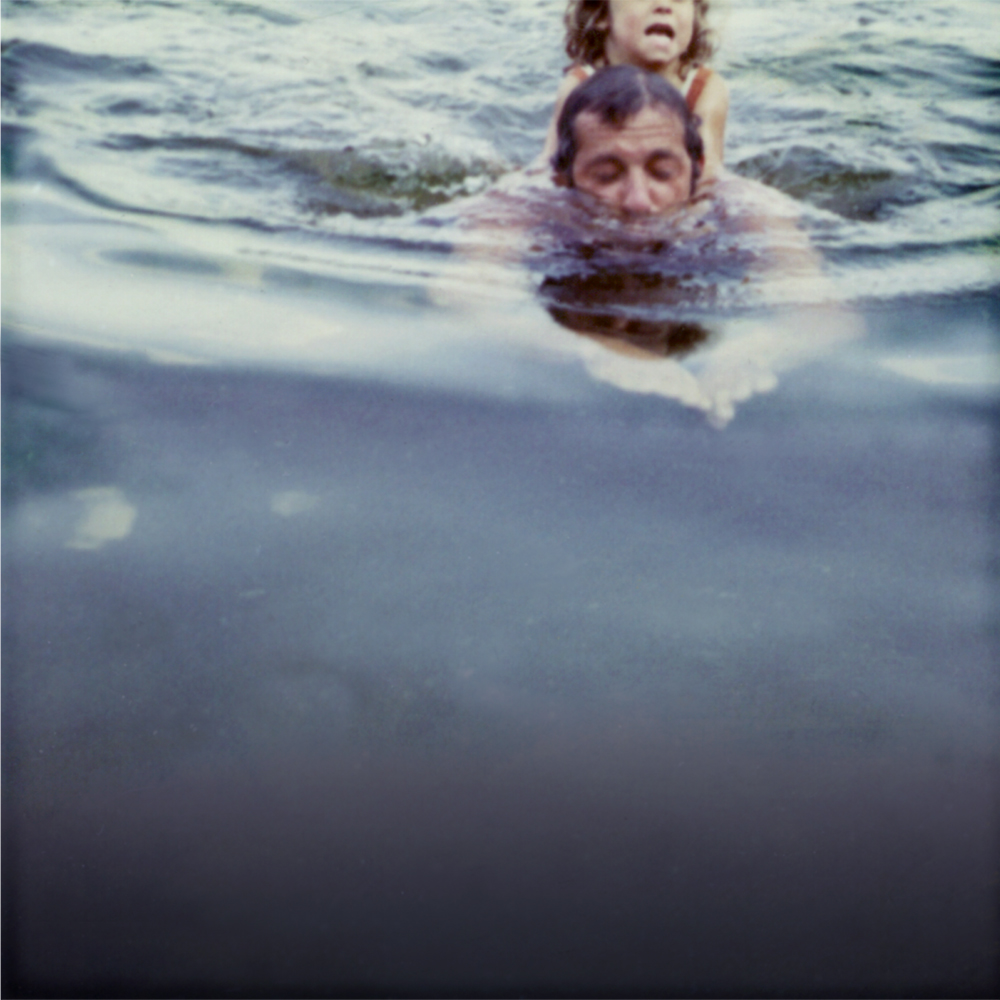

Sixes and Sevens, 2001

While I was having silent

underwater tea parties,

lives were lost

taken

children and men

both good and bad.

Mothers too, disappear.

I could have been six or seven,

or not at all

on a horse

or a train,

I could swim for days and not get cold.

You know that photograph –

the one by the lake

there’s a shadow in the water

or it could be a bird flying over head

it’s out of focus, anyway

that’s where I drowned

or could have

while you weren’t watching.